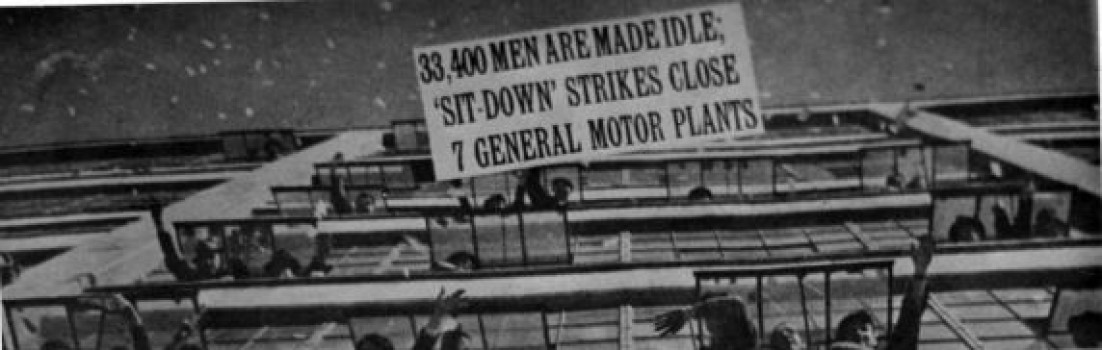

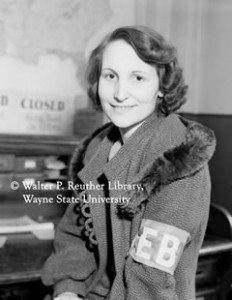

Interview with Genora Johnson Dollinger, lead organizer of the Women’s Emergency Brigade at the Flint sit-down strikes. Dollinger recalls the famous “Battle of the Running Bulls” when police—bulls—tried to regain control of the GM plant by force. Overwhelmed, and afraid to shoot at women, the police abandoned their assault.

Genora Dollinger: And we had the water hoses from the plant, and the hinges don’t—that’s all. Those hinges were kind of heavy hinges. You know, the old car-door hinge was a different thing. And they got the big boxloads of them and they got them down to look so they could fire them from downstairs, and they were upstairs on the roof firing them, too.

Now, we didn’t have any—the sock and the blackjacks would do no good. There was no hand-to-hand combat. And those—they had rifle shot and buckshot. There was firebombs and those tear gas canisters. And we would run out and grab—the men were much faster at that, and bigger. I mean, they were better pitchers. They would get those. I didn’t try anything like that. They’d get tear gas canisters and hurl them back. And the firebombs, they usually got those. I mean, they attempted, but the timing on those was very important.

So this went on. This was all we had. That was all there was to the goddamn thing. And I know that going in these doors like this, you’d come in a swinging door and see one person come out, and you’d go in, that the habits are so ingrained that at one point, when I was going through it, a man was coming out, he tipped his hat at me. I never forgot that. I thought, of all things, you know, tipping his hat.

So anyway, the sound car was down there, and we had Victor Reuther as the primary speaker. And then he would pull up other men, making their appeals, and this went on and on. It never dawned on me, you know, to speak. In the first place, this was primarily a man’s operation, and I’m down there helping out, although I never thought too much about men and women when we were right in the heart of a battle, come to think about it. But it never dawned on me I’d never made any kind of a public speech over a microphone, and it—until he came back and told us. He said, “Well, we may have lost the battle. The war is not lost, but we may have lost this battle.” And he gave us the idea that we had to prepare people for, you know, this little defeat. And I said to him then, I said,“Well, Victor, why don’t I speak over the—why don’t I talk to them over the loudspeaker, if the battery is going down.” And he says, “Well, we’ve got nothing to lose.” He had great confidence, too in women. They all had—they really didn’t feel that women were too much, that we were good, wonderful women for wanting to help them. So that’s when I got up to take the mike. And, again, there, you lose yourself. You go beyond yourself and think of the cause. And I was able to make my voice really ring out on that one because I knew that battery was going down. We only had a few moments left. And so, that’s when I appealed to the women of Flint. I bypassed everybody else then and went right to the women and told them what was happening. And that’s when I said, “There are women down here, mothers of children,”and I made it sound plural, because I knew that here was this gallantry that’s always present in the hearts of men and other women that are going to come down and stand by women in such a situation. So that’s when I said,“There are women down here, mothers of children, and I beg of you to come down here and stand with your husband, your loved ones,” you know, “your brothers, and even your sweethearts,” because we had a lot of couples going together, and I’d get their girlfriends.

And when I made that appeal, it was a strange thing. It was dark, too. But I could almost hear a hush. There was a hum-hum-hum-hum at both ends. I could hear a hush over that crowd the minute a woman’s voice went over. It was startling, you know. All night long, they didn’t know there was even a woman down there.

And as that happened, I thought saw—I don’t know whether it was car lights. Whatever it was in this darkness, we could see the action going on up there. Probably, maybe they were factory headlights or spotlights on us or something, police lights. But I saw a first woman struggling, and I noticed that she had started to come down, and a cop grabbed her by the coat and she went right out of that coat. And this was in freezing weather, freezing weather. There was ice on the, where it had melted, icy pavement and everything. And she just kept right on coming. And as soon as that happened, other women broke through, and again we had that situation where cops didn’t want to fire into backs of women. And once they did that, the men came, naturally, and that was the end of the battle. [4].

Roscoe Van Zandt:

Roscoe Van Zandt, who sat down at Chevrolet 4, is the only Black worker known to have participated inside. The first night he stayed to himself, but by the next day, because he was older, the workers had voted that he should take the only bed in the plant. When they marched out on Feb. 11, still patriotic to the government that had fired on them, it was Van Zandt who was chosen to carry the U.S. flag.Van Zandt later spoke to Black churches about the strike and the UAW. [5]

Don Dooley

Don Dooley has worked at Fisher Auto Body since 1927 and has spent much his time in the paint department. Dooley joined the United Auto Workers in 1935 and has held several offices including the presidency of UAW Local 95. Of joining a Union he says:

” Well, I probably decided I was going to join the union the minute I heard somebody was trying to form a union. Like I said before, the company attempted to form a — what they called a company union at that time, and then of course we started hearing about the UAW being formed, and I knew then that I — I was going to belong to the union. And I can’t recall just how soon after I first heard that they were, because it was kind of — a lot of it was done on the quiet for a period of time, you know. They — they met in guys’ houses, and that might have only been six or eight people. I didn’t happen to be one of them. There are guys in Janesville today who you could go to and get much more information about that particular time than I can give you, because I wasn’t one of those that was a ringleader in the starting.”

Of his working conditions, he states:

“Probably one of things we would have talked about the most was the working conditions in the spray booths, some of the jobs we were made to do and didn’t get paid for them. For instance, we’d have to come in in the morning and climb a big steel ladder and go up on top of the spray booths, turn the motors on to start the eliminators. We’d have to run a little paint out of the paint lines. All this before the whistle blew and before — and you didn’t get paid for it. And the same way at the close of the shift, because you were on piecework, see, and you only got paid when you pulled the ticket off the job, and you wasn’t pulling no tickets off the job until they started the line. All that stuff had to be got in readiness before you started to work.”

To listen to the testimonies of Geraldine Blankinship, Pauline Polsgrove, Richard Weicorek, and James Todd, click here.

To hear/read more workers’ testimonies click here.